Anti-sacramentalist Protestants and the ripe old age of a poet

My friend Michele sent me a note recently. In it was copied a brief reflection by Dwight Longenecker. In his own words: "Brought up in an American Evangelical home, I went to Bob Jones University . . . . While there I came down with a severe case of Anglophilia from reading too much C.S.Lewis and Tolkien and T.S.Eliot. . . . was ordained as an Anglican priest and stayed in England for twenty five years. After ten years wearing a dog collar I was received into the Catholic Church."

In short, he's a Bob Joneser fundi who found Rome-sweet-home by way of Cantebury.

Michele asked me what I thought of his main assertion, that Protestants can't produce good art because they lack a sacramental belief system. I don't have any energy these to pick a fight with someone like Longenecker. I have too many friends who've converted recently. My emotional tank is low. I'd rather figure out how to stay good friends. Shooting at your friends at close range is a loud and bloody business. If we can't be friends, I'd rather we walk away from each other peacefully and pray that God cross our paths at some future point, maybe in the third generation post Vatican II.

I did have a few thoughts, though, mostly to sharpen my brain. I offer them as an amicable response.

Here's Longenecker's key paragraph:

"Protestants have problems with [sacramentalism]. They're suspicious of the physical. They're semi-Manichees . . . . Protestants don't have sacraments because they don't believe God interacts through the physical like that. They also don't like the messy miraculousness that comes with sacraments. So they retreat into a safe, intellectually abstract religion of theology and the Word, and take refuge in head games. Out of this comes an art that can only ever be functional--e.g. illustrations for Bible story books, or didactic e.g. pictures with Bible verse captions."

My initial response is yes and no. Yes, this problem exists in Protestant cultures, but no, it's not a fully accurate description.

The main problem with his comment is one of over-statement. He tries to say too much in too little space. He takes the term "Protestant" and uses it to describe all Protestant behavior, here in relation to art. But it's silly. Are all Catholics the same? No. You have your liberationist Catholics, your feminist Catholics, your rad-trad Catholics, your folk Catholics, your literati Catholics. Surely these will not all manifest the same attitudes about art. But from either zeal or ignorance we box entire traditions into a single, all-encompassing statment and hope that the reader will be persuaded--and I don't excuse myself from this habit.

The second problem with his comment is one of false deduction: the conclusion does not follow categorically from the premise. The argument, if I've read it correctly, is this: that a sacramental system of belief is necessary to produce good art; "Protestants" do not believe in such a system (they believe in "safe, intellectually abstract religion"); ergo, Protestants cannot produce good art. In actual fact, Longenecker really tries to tackle too much in his pronouncement, and since they come in blog form, perhaps it's unfair of me to nitpick. But it pushes me to ask hard questions about my own tradition, so I'll take it as an exercise in mental calisthenics--which, in truth, isn't such a bad deal since the root of that word, kalos and sthenos, suggests a beauty of strength. I'm going to try to beautify my mental muscles.

So then . . . .

In every major tradition, whether Protestant or Catholic or Orthodox, you have tendencies. The genetic code of the tradition makes us inclined to this or that thing. Some tendencies are healthy (the love of the Scriptures), some are not (hyper-individualism), and we all have both. As an evangelical Protestant I need to learn about my basic tradition, and whatever sub-traditions I have grown up in and alligned myself with, so that I can keep myself from sliding into unhealthy tendencies. In the case of art, I need to watch against rationalism and pragmatism.

We also have syncretistic tendencies inside of us. In these we meld the Gospel with fallen aspects of our human cultures. Whether we syncretize with the American Trinity of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness/property or with the Mayan gods in the highlands of Guatemala, it's always a danger. My point is that while Protestants struggle with tendencies that make it difficult for them to make good art, they are only tendencies and not, I contend, fatal diseases.

A second thought is this. Before the 16th century we, Reformers and Romanists, were all Western Christians. Thus, the heritage of Anselm, St. Francis, Julian of Norwich, Augustine, Athanasius and Origen is all ours in common. As Protestants we can claim the writings of the early church fathers and the many blessed practices of Medieval Christians as ours too. (Not all things Medieval are creepy and religiously lugubrious. You have Gregorian chant, the mystery plays, gothic architecture, Bernard of Clairvaux's Song of Solomon sermons, Franciscan canticles.)

This is our soil too and it is a soil rich with sacramental minerals.

Which brings me to a third thought. Catholics are not the only sacramentalists in Western Christianity. Anglicans, United Methods, and Lutherans, among others, happily claim a sacramental identity. That these identities diverge from a Catholic identity does not deny a common embrace of a sacramental spirituality as defined by Longenecker and other Catholic thinkers. To the point, the belief that "grace flows through the physical world" is not antithetical to a Protestant Christian understanding. How such a belief is interpreted and applied is where we begin to take different paths; it's what determines where we land in our religious and artistic behavior.

Thomas Aquinas described the human creature as a homo viator, as a wayfarer, a wanderer. The Catholic writer Walker Percy believed that "the Catholic view of man as pilgrim, in transit, in journey, is very compatible with the vocation of a novelist because a novelist is writing about man in transit, man as pilgrim." Flannery O'Conner, the iconic Catholic writer of the last century, said that the Catholic novel "can't be categorized by subject matter, but only by what it assumes about human and divine reality"--i.e., that we are seriously messed up creatures in need of a grace that can only come from a God who takes on human flesh, hiding his divinity in the unseen cracks of ordinary life, and makes blessed meaning out of our painful experiences. I deeply resonate with these thoughts, as with those of von Balthasar, Viladesau, Tolkien, Graham Greene, Maritain, Chesterton, all Catholics, and at the level of theological aesthetics I do not find them incompatible with my Protestant beliefs.

More to the point, I'm not simply borrowing or falsely importing these ideas, I'm recognizing them as true to my own culture. They too would grow naturally in the soil of my tradition if only given a reasonable chance. They'll manifest themselves in different ways, but only in the way that apples breed into many forms of apple-ness.

In her essay "Novelist and Believer," tucked in her wonderful book Mystery and Manners, O'Connor makes the following observation:

"What I say here would be much more in line with the spirit of our times if I could speak to you about the experience of such novelists as Hemingway and Kafka and Gide and Camus, but all my own experience has been that of the writer who believes, again in Pascal's words, in the 'God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob and not of the philosophers and scholars.' This is an unlimited God and one who has revealed himself specifically. . . . It is one who confounds the senses and the sensibilities, one known early on as a stumbling block."

My fourth thought relates to Pascal's comment. Our art work as Protestants can experience an infusion of en-earthed grace if we do a good job of paying attention to the Old Testament. And is the OT not ours as much as any Christian's? Do we not find here what Franky Schaeffer called the "dangerous, uncivilized, abrasive, raw, complicated, aggressive, scandalous, and offensive" quality of God's people--of God's own choice in literature?

And what better voice for such earthiness than Frederick Buechner, a Presbyterian. Graham Green and Francois Mauriac, as recognizably Catholic writers, have sublimely incarnated this idea in The Power and the Glory and Viper's Tangle respectively, but Buechner holds his own at the table with such works as The Son of Laughter, Brendan, and Godric, the latter of which was nominated for the Pulitzer in 1981. His stuff is so earthy it makes me squirm. But I also taste grace in all the mucus and dust off the lives of his characters.

Fifthly, there is the Incarnation. You needn't the apparatus of the Magisterium to appreciate the enfleshed grace of Christ. The liturgical and mystical enviornments of the Catholic Church can enhance your apprehension but they do not preclude the Protestant from feeling the deeply disturbing, deeply nourishing mystery of God in the flesh. TheAnglican bishop and biblical scholar N. T. Wright has performed an incalculable service of leading pastors and lay believers into a truer, and indeed multi-sensory, understanding of the Jewishness of Jesus, which has often invited us back into a renewed experience of the Hebrew culture with all its bloody and mirthful feasts.

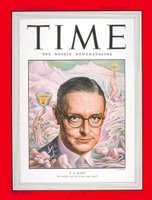

Sixthly, and finally, I would reiterate what I've said previously: there are plenty of Protestant artists making good work, and there will only be more of them in years to come. I've wrestled with the question of our evangelical tradition elsewhere, so I'll not repeat myself here. (Evangelicals and the Arts: Part I, Part II, Part III. Also: Our future in 2056. And then: Can we make great art? and Part II of that.) All I'll say is that the cloud of witnesses in our tradition ought to encourage our hearts and spur us on to love and good deeds, in this case, to make the greatest art possible. Our fathers and mothers include, among writerly artists, George Herbert, T. S. Eliot, George Macdonald, C. S. Lewis, Dorothy Sayers, Madeleine L'Engle, Frederick Buechner, Luci Shaw, Annie Dillard, Wendell Berry, Walter Wangerin, Stephen Lawhead, Calvin Miller, Virginia Stem Owens, Robert Cording and Kathleen Norris--and surely a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist counts as reasonably good art.

In the end, I see two important questions. One, can our Protestant theology nourish great art-making. Two, can our Protestant churches nourish great art-making? I think the answer to both is, yes, within the great ecology of Protestantism, it is possible for great art to emerge. It has happened already, it is happening today, and it will continue to happen, though not without great sacrifice and slow-going labors.

In recent decades a term has come into prominence, the "evangelical Catholic." The term is used to describe a Catholic believer (the noun) with strong evangelical tendencies (the adjective). I think, however, that it can go the other way, a "catholic Evangelical." I would think of myself in this way. I see myself as a Great Tradition Christian who seeks to identify himself with the creeds and the historic Church. As I avail myself of this larger tradition I find my roots strengthened. I find my imagination enriched. I find myself looking for all the ways in which grace sneaks through the twists and turns of my quotidian life as well as in global and cross-cultural, historical events. It's a work in progress, I know, but I am hopeful, and I feel greatly encouraged by my goodly traveling companions.

And now for a swift detour.

What is the ripe old age of 12 debut poets?

I've started receiving the publication Poets & Writers. In the latest issue they have an article titled "Finishing the First." It features a dozen poets who have had the experience of publishing their first book of poetry. Do you know what the average age is? Just guess. Look away from this blog and guess.

Ok, now I'll tell you. It's 39.

Alright, it's not scientific and the people they picked are perhaps random. But not as random as we might think. The ripening process for a poet is much longer than a rock n roll band, which I'm guessing is circa 23. (Bono was 21 when "October" came out, 23 with "War".) The thought sobers me. It takes a long time to figure words out. Ooph.

And lastly, my friends Mike Akel and Chris Mass.

Their film Chalk is showing right now at the Austin Film Festival. To their great surprise they won the big prize: Best Narrative Feature, awarded by the jury. It's highly unusual for a hometown option to win the ribbon. Here's a nice article in the Chronicle.

We've been praying for the artists at Hope Chapel for many years. Mike and Chris are the first filmmakers, after many years of boring, awful, tedious labor, to punch through the amateur ceiling into the professional ranks. They've just signed a picture deal with Universal to write and direct a little-league baseball mockumentary. We're proud of them. But perhaps mostly, we're proud of their hearts. They continue seeking ways to love and serve the other artists in our community, even as we all keep looking for good ways to serve each other with a gracious, generous love, no matter the skill or accomplishment.

No matter how famous or rich any of us become, there's no place for cool or diva here. I won't tolerate it. If you're the Great And Powerful Artist and you have a rotten heart, you're no good to anybody. From day one we have to keep cultivating a humble heart. And I think that's what Mike and Chris have done such a good job at. And I can't tell you how refreshing that is.

Comments

I've read a few places now about the 'Protestants can't make good art because of their theology' argument. I have a great love for Catholicism, but I can't help but see this as a blindness to history and art itself. Do protestants get Shakepeare, or do we say that Shakespeare was a closet catholic--how are you going to argue that he was sacramental and that it was because he was Catholic?

Is Gilead a Catholic novel now because it finds the spiritual in the everyday?

But I think the primary move here is that Catholics get to look at all of Western Civ while when they consider Protestants they only think about contemporary American evangelicals--and see a very pragmatic, profit-driven output that has more to do with American culture than differences in theology.