Retreat News: Wherever do we get our ideas about what an artist is: Part I

"Artists should see nothing as it is, but fuller, simpler, stronger: to that end, their lives must contain a kind of ... habitual intoxication." -- Nietzsche, The Will to Power

The sublime "is formless, exhibits no purpose, and is apprehended in a state of excitation, 'a momentary checking of the vital powers and a consequent stronger outflow of them." -- Edith Wyschogrod, citing Immanuel Kant's Critique of Judgment

What is a teacher?

If you asked your average group of Christians, and assumed the best kind of average, to answer the question, "What is a teacher?", you'd probably get a reasonably high degree of agreement from the answers. What is a farmer? A farmer is someone who, all things considered, cultivates land or "husbands" crops or animals. What is a doctor? What is an airline pilot or a chef? These are the kinds of occupations that prove fairly easy to describe, even if in the actual writing of an answer we may fumble around for right descriptive phrases.

What is an artist?

What's an artist? That's the more difficult to describe. Part of the difficulty lies in determining whether we are speaking of "artist" in terms of a vocation or an occupation, or a profession or, in Christian circles, of a ministry. The same difficulty, of course, might be involved in the case of a farmer or teacher. It isn't a 1 or a 0 matter, because we're talking about a range of meaning. We're talking about a range of options on a spectrum, not a point. But with "artist" things seem to be a little more complicated. The vocation of the "artist" is difficult to describe because it occupies a highly fluid identity in contemporary society, let alone in the church.

(Read Rolling Stone mag, The New York Times arts section, People magazine and the latest edition of your favorite Christian magazine and you'll know what I mean.)

Trust me, I've tried this out with audiences for years. I say, "Write down "What is an artist?'" And five minutes later I ask them to share their answers with the group. The definitions are all over the place. You should give it a try. It's fascinating business. And I don't think we would run into this problem with "teacher" or "farmer."

How are we to think of the vocation of the artist?

As a craftsperson? (as per technician)

As an original genius? (as per Kant)

As a self-expressive visionary? (as per Nietzsche)

As a co-creator? (as per Sayers)

As a reverent mediator of the divine? (as per Tillich)

As a responsible servant? (as per Wolterstorff)

As a prophet? (as per Deborah Haynes)

As an imitator of nature? (as per classical Greece)

As a priest of creation (as per Graham Ward)

Yes. No. All the above. Sure, we can say all the above but the fact remains that most of us are probably running around with a certain definition in our head that functions as dominant.

We might answer that context matters for our understanding. If by day I paint for a Chelsey gallery and by night I play for the New York Philharmonica, and on the weekends I make wood cabinets for the neighborhood hardware store, then, well--I guess I'm a pretty impressive artist. But I'm also thinking of myself in different ways with respect to my three contexts.

Our ideas about an artist?

Contexts matter. But so do conceptual histories. Our ideas about what it means to be an artist do not come from nowhere. Ideas have a history as well as hidden inertias. Those culturally embedded histories give a particular shape, and force, to the meaning of ideas. The idea of the sublime, for example, originates chiefly in 18th-century British and German philosophical settings.

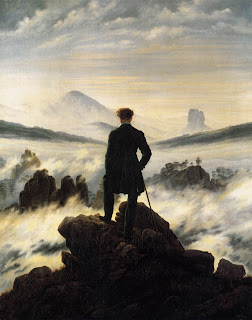

Kant distinguished the mathematical sublime from the dynamical sublime: the feeling of smallness in the face of massive size and the feeling of smallness in the face of massive power (which painter David Caspar Friedrich repeatedly evoked in his work, as seen in the three works I include here). Many of the ways that folks today use the term, however, have no sense of this history. But the idea of the sublime isn't neutral--in particular as it relates to our ideas about art and beauty--and we need to be careful in our use of it, lest we perpetuate notions of the vocation of the artist that run against the demanding patterns of the gospel.

So what does it have to do with our May retreat?

Stay tuned. I'll post part two of this entry on Friday.

Comments

An artist is someone through who's work/efforts/output, those who witness/consider/ponder said work/efforts/output are able to experience that which is transcendent and speaks to matters of the soul (existential issues, core longings, spiritual realities, etc.).

Does that work?

Ben: I think that could be the beginning of a good understanding. You capture the complicated business of art well with your various phrases. The two terms that would require careful unpacking are "transcendent" and "soul." Neither is particularly self-evident and both have, if you will, a troubled history. The different ways that they've been interpreted and applied with respect to the arts is an occasion for slow, careful disciplined thinking. But do keep at it.